The Beginning of an Ongoing Story…

It all begins with an idea.

I first learned about Autograph: ABP while visiting the Black Cultural Archives. I was in search of examples of queer-led organisations, as I planned to create one of my own, Home Studio. As I explored, I realised that foundational members of Autograph who identified as queer, such as Sunil Gupta and Rotimi Fani-Kayode, were absent from the archive.

Upon further investigation, I learned that when the BCA was established, its leadership chose to exclude Black and Brown queer archival material.

While visiting the Black Farmer’s Shop in Brixton Market, I spoke to a local man I had seen frequently walking around with a book he had written himself and a tie that read, “I love Jesus.” We had performed at the same open mic one evening with Poetic Unity, and his piece had woken us all up. As the first performer of the night, he had us standing and chanting affirmations, energising the audience and the other performers for a lovingly vibrant evening.

After grabbing a coffee, we sat and chatted about our personal histories, the history of the Black Cultural Archives, and our encounters with queerness. I was careful not to probe too deeply into the topic of queerness, as my experience discussing it with older Black people had often been fraught. But I’m American, so once he mentioned that he was a friend of Len Garrison, the founder of the archive, I asked him directly why he thought his friend had chosen to leave out queer history.

His response was to tell me a story—a classic one—about his mother, and how his community’s guidelines had shaped his understanding of her queerness and how to respond to it. Growing up between the Caribbean and the UK, his father, like many others, had left the island for the UK in search of a better life. Once his father was gone, a woman moved in—his mother’s “special friend”—with whom she shared a room. When his father returned, his reaction to their relationship made it clear that this woman was more than just a friend. When it was time for the family to leave for England, his mother chose to stay on the island with her partner. This, of course, was deeply upsetting for him as a child, and the community’s response was to simply not talk about it. They did not include this story in their history.

The telling of this story gave the impression that Len Garrison might have experienced something similar, which could have influenced his decision to exclude queer history from the archive.

But we need these stories! I needed these stories. So I sought out those who had been excluded and aimed to record them. That is when I met Sunil Gupta.

I met Sunil, and subsequently his husband Charan, at their home in Camberwell, remarkably close to where I had lived when I first moved to London in 2020. I used to run past his house, grab a coffee, and hang out nearby, completely unaware. There are so many overlapping universes in this city; it is a wonder.

Sunil’s house was well-lit but grey due to the weather—a beautiful, open space full of plants and separate offices partitioned by bookshelves and archival boxes. After coming up through the vintage OTIS gated lift, he offered me a cup of tea. “Herbal or English?” he asked. “Herbal,” I replied, but he didn’t hear me, so I stepped closer under Charan’s instruction. “Herbal, please,” I repeated. “Is it okay if I look through your books?” “Yes, of course,” he said. “There are some new ones on the coffee table.”

I started there. The newest editions of Tom of Finland and Come Out sat at the top of the pile. Images of gay men filled the pages, cool and elegant. Their confident postures reminded me of the images I’d seen online that Sunil had taken for the Helmut Lang campaign, in street photography style. Soon, Sunil brought my tea and biscuits and sat down to begin our conversation.

Managing my anxiety as meditatively as I could, I told him about myself, about Home Studio, my interest in Autograph: ABP, and why I was so curious about its history. He seemed puzzled, and I worried that I wasn’t making sense. I often feel this way when talking to English people or those who have lived here much longer than I have. But he understood me and was curious about the nature of the workshop I was proposing, as I had left that part out. I told him about the last two workshops we had run with Ajamu and Bilan, and explained that it could be whatever he wanted it to be. It could be a collaboration or solo, focused on his current work or whatever he wanted to discuss with an emerging artist. I mentioned the pop-up darkroom idea and the possibility of hosting a making session. He seemed intrigued but still a bit unsure, so I asked him to tell me about what he was working on now and reiterated my somewhat selfish desire to hear his story about ABP.

He told me that he had stopped shooting analogue. This surprised and saddened me, as it ruled out the making session. He explained that analogue photography had become too expensive and that his painter friends could sell their work for thousands, creating a larger return on investment—a privilege photographers did not enjoy. While he expressed no regret about being a photographer, as it suited him and his needs, he acknowledged the economic reality.

Then he began to tell me the story of ABP and how it started with a group show curated by Monika Baker in 1986.

Before we delve into that story, I would like to introduce my project—my access point and excuse for all this exploration.

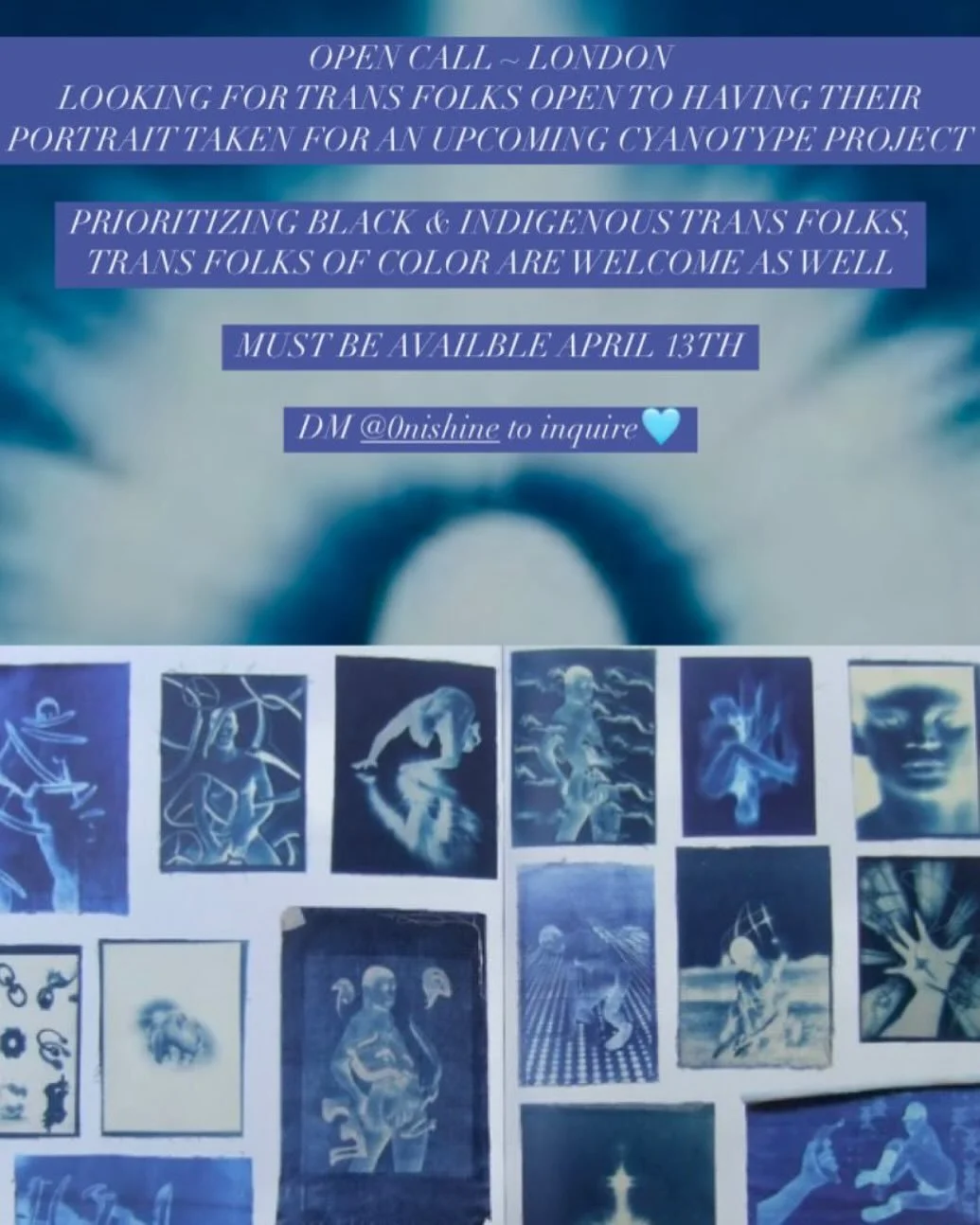

Home Studio was born from a need to survive and a desire to thrive in the professional art world. It is a community of care for queer and trans artists of Black African/Caribbean and Global Majority descent.

Home Studio simulates the studio and residency experience by granting access to a network of established artists, hosting critiques, making sessions, photo walks, and other nurturing events that empower, develop skills, and promote the QTPOC creative community.

We intentionally prioritise Black African/Caribbean people, Black art, and Black thought in our efforts to dismantle structural and systemic anti-Blackness. You will see this in our messaging, our community, and our very being.

We do not aim to discourage or make invisible Global Majority folk—nor to lump everyone together—but rather to unite, as the word Black once did during the Pan-African movements of the mid-20th century, the Afro-Asian Solidarity movement of 1955, the Third World Liberation movements of the 1960s and ’70s, the Anti-Apartheid movement from the 1970s to the ’90s, and the Black Lives Matter movement of the 2010s.

I started this project because I needed community and space to grow my practice. I didn’t find it within residency applications, studios, or funding for my PhD. So I channelled my resilience into subversion, finding alternative ways to meet, gather, and use my gift for organising and networking to benefit young queer artists of colour. It just so happened to work in a city that I am not from and am still learning to navigate.

By directly asking institutions with unused space to host workshops run by my friends and mentors, I secured deals with Queercircle, Lewisham Arthouse, the LGBTQ+ Centre, and Auto Italia.

My life goal is to one day open a permanent space (one of those 99-year leases) dedicated to Black African/Caribbean and Global Majority art and community. We aim to address the underrepresentation of our community within the art world by developing, promoting, and empowering artists of our time who are deeply rooted in histories of liberation.

Now, back to Sunil’s story…

Autograph came about through the curatorial and organising work of Sunil Gupta and Monika Baker. Their exhibition, Reflections of the Black Experience, was held in 1986 at the Brixton Gallery. Following the exhibition and its programme, attendees lingered, waiting for more opportunities to emerge. Twelve of those who stayed became the cohort that signed Autograph into its legal status.

He told me about his time in America studying business, his family’s move to Canada, and his later move to London to study at the RCA, where he began building his photography career. He has recounted this history many times, and Louisa Buck’s interview with him for a-n provides an excellent record.

I hope you don’t feel too slighted—all researchers cheat—but I promise I have another story for you. This one is about the artist who ignited Home Studio and inspired me through his appreciation: Ajamu X.

Intergenerational Mutual Appreciation

It all begins with an idea.

Recently, Izzi and I were invited to participate in a shoot with photographer Ajamu X. We have been visiting Ajamu’s studio for almost a year now, participating in a weekly boxing session for Black queers and was the first to host a workshop with Home Studio.

Witnessing each other's strengths and weaknesses, a sense of belonging brewed in the heart of Brixton. Ajamu has effortlessly become a mentor, a sound board for ideas, a collaborator and an inspiration.

Every Monday, he greets us at the door with a smile and a "How are you doing, lovely?" starting our weekly challenge with positivity. Even through text or email, he insists on checking in on how we are doing personally before getting down to business. This level of care permeates throughout his way of working, and as we began our photography session, I continued to feel his warmth.

As I partially undressed, I began to realize how comfortable I felt in my body. Living in London has changed me in ways that Florida could not have prepared me for, with its slow pace and constant heat. Here, my shoulders are usually coldly tense, preparing for any potential disappointment like missing a bus, sudden rain, or a canceled meet-up with a friend. Too often my heart is usually heavy with nostalgia and grief, mourning versions of myself that I’ve had to let go of and those who have let go of me. But here it is different.

“You know the feeling when you take your socks off at the end of the day, rubbing the indents they left on your skin? The relief your toes feel in the new context of freedom. This is how it felt to be half-nude in his studio. This appreciation for exposure carried us, in the soft light just above the black box we struck our poses in. What was there to be shy about? What is bashful about liberation? What can shame do to esteem, praise even?”

I believe that this is the work of kink. It takes pleasure in the non-conventional, sometimes hidden, sometimes averted. My pleasure was found in the feeling of being seen as whole. Ajamu knows my intellectual interest, my aesthetics, my power, and my insecurities. Now he is getting to know my body, my intimacy, with the same interest and care as every other characteristic. He was always listening, checking in, making corrections, pushing us into beautifully awkward shapes as well as capturing the natural tenderness between my spouse and me.

The day before, my mother sent me two articles on the health risks associated with lesbian sex and male-to-female transitioning. The day before that, she sent me a homophobic sermon via YouTube. In response, I sent her a queer-friendly sermon by a pastor in Harlem who spoke on church trauma and loving all people as they are. She then sent me a conspiracy piece about the NY pastor in which she claims that he doesn’t believe Jesus is God and therefore is uncredible. There were no words between the messages. Just links, no listening.

I told this to Ajamu after our shoot, as he is familiar with my mother's and my estrangement. We talk about how these formative relationships have such a profound impact on how we view ourselves, forgetting to appreciate the parts of us that have been disapproved of. He reminds me that we cannot afford to live in fear and shame. It is better to accept and keep going rather than praying for something ideal when it has never existed.

While lying on my back, curling and stretching my toes on my partner's chest and in her hands, I feel love for the pieces of me that have been demonized. I see my sexuality as a source of power that I have the agency to wield when I please. The camera clicks, and I am certain that this moment will live on forever.